Transition Mode

*Disclaimer : All opinions of this experience are my own and not representative of the U.S. Government or The Fulbright Program.

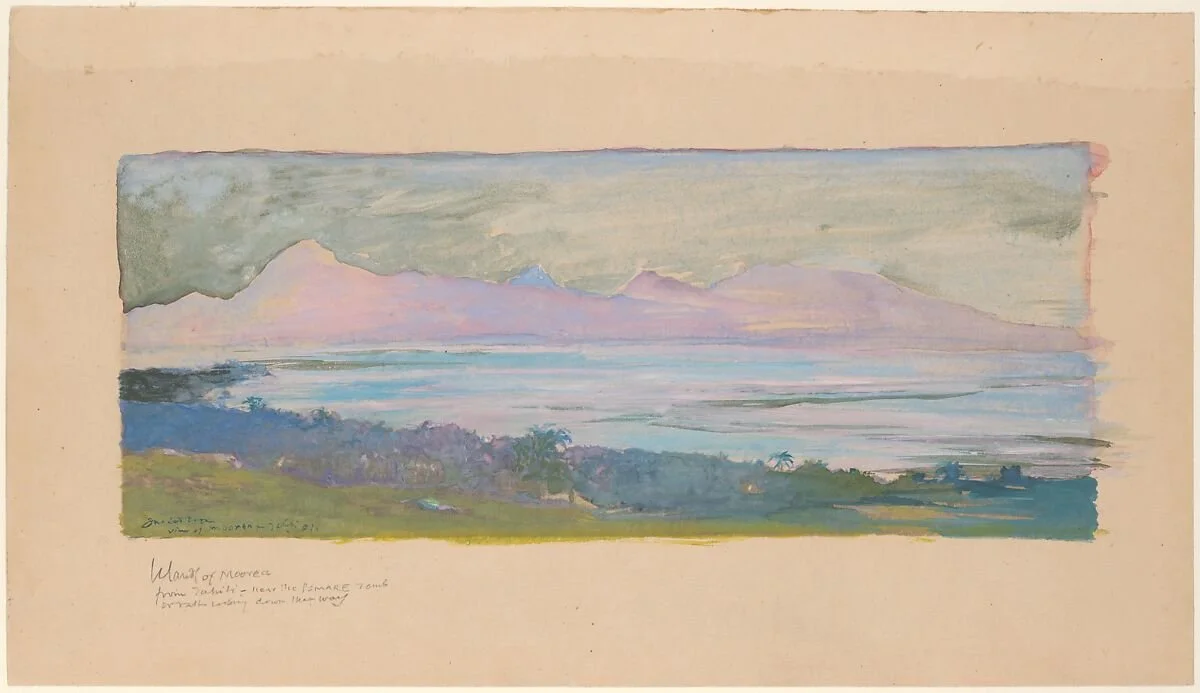

Cover Image: “Entrance to Taukira River, Tahiti” John LaFarge, 1893, watercolor.

Today marks ten days since I moved out of my beloved college town of Rochester and back home to the Berkshires for a few weeks before departing to France. I leave in less than two weeks and am very excited. During this time, I am sorting through my belongings, loading a storage unit, and preparing to leave home for three-quarters of a year. Even though there’s a lot to shuffle through, I have made time to help out back home, organizing tools, replacing saw blades, and even cooking seven pounds of bread dough.

Even though it’s hard to keep my brain empty from all the exciting anticipation, I am working through some creative ideas relating to my project. I keep reflecting on overseas territories with unique artisanal ties to France. More specifically, French Polynesia. I picked up a book at a book swap way back in high school called “John LaFarge’s Second Paradise” from Yale University Art Gallery. I was drawn to it for the pastel blue cover with delicately painted palm trees. I barely looked at the book again once I left for college, and almost nine years later, it is relevant to me again.

John LaFarge (1835-1910), was an American Impressionist who was an illustrator, painter, and stained glass artist. He was a rival of Louis Comfort Tiffany and a contemporary of John Singer Sargent. He traveled extensively throughout Asia and the South Pacific. His travels in the South Seas are covered in the book I own. Initially, I didn’t realize Tahiti and other islands in the South Pacific were part of French Overseas territories. Once I learned this, I sought out Paul Gauguin’s paintings from the end of his life, as he died in Tahiti.

In these smaller dives, I have uncovered the complex nature of Gauguin’s life in Tahiti, and that while his works represent something that would have been innovative during his time, they erase any influence of colonialism, racism, and sexism. This led me to wonder why he fled for Tahiti in the first place, with various articles noting his seeking “primitiveness” from the islands. Unlike John LaFarge’s time in the Pacific, which is littered with sketchbook studies, and a more academic approach to his work…as he would later use his travels to influence his stained glass… Gauguin, as many European artists would do, appropriated other cultures’ present and early civilizations as context for the Primitivist art movement.

Today, Tahiti and other islands of French Polynesia represent a significant space of biodiversity, known for ecology in tropical rainforests and coral reefs. It is still a revered destination for tourism and is still a flourishing space for various flora and fauna. It is still a hub for experiencing Polynesian culture and hosts many native artisans continuing their traditional crafts.

Many of my “big picture” questions regarding my ceramic work revolve around cultural appropriation versus appreciation as an academic creator. I come from a French and Dutch family heritage that colonized and caused devastation in South Asia and the Americas, in the name of greed and superiority. I married into a culture over 9,000 years old, full of diversity in religion, color, people, and craft. While abroad, I hope to find more techniques and resources for well-rounded research. I hope to pass these techniques on to my future students.

Images Included: The Island of Moorea, John LaFarge, 1891, Himene at Fara, John LaFarge, 1891, Tahitian Women on the Beach, Paul Gauguin, 1891, The Three Huts, Tahiti, Paul Gauguin, 1891.